Maynard Reece and a King Named Buck

“Hope” is the thing with feathers. And during more than ten decades, feathered things, waterfowl in particular, informed the art of the great wildlife painter, Maynard Reece.

If you don’t know the name, you’ve seen the work. Probably no other artist did so much to capture that breath-holding moment when a waterfowler experiences ducks or geese “cupped and webbed,” setting into the decoys spread in front of him. From out of the canvases you can almost hear the beating of wings.

Reece died at 100 this July in the place where he was born, Iowa. The son of a Quaker minister, as a boy he moved a great deal around the marshes of the northwestern part of the state, beneath the wide band of the Mississippi Flyway. Too poor for formal training, Reece was essentially self-taught and winning blue-ribbons by the time he was 12. After high school he studied and drew the wildlife on display in the state historical museum in Des Moines, where his talent was recognized by a publishing company; and he became a professional graphic artist.

Reece painted and drew almost every kind of mammal, fish, and fowl; but ducks and geese were never far from his heart as he worked for some of the famed titles during the Golden Age of magazines. Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling was a pioneering conservation activist and Pulitzer-winning editorial cartoonist, as well as a resident of Iowa, who took notice of Reece in the 1940s and mentored him in wildlife art, leading Reece to winning the 1949 competition for what is still universally known as the Federal Duck Stamp–Darling having drawn the very first in 1934–one of five wins for Reece across the next four decades. And Darling was there for Maynard’s third, and arguably most famous, win in 1959, instrumental in a roundabout way for its coming to be.

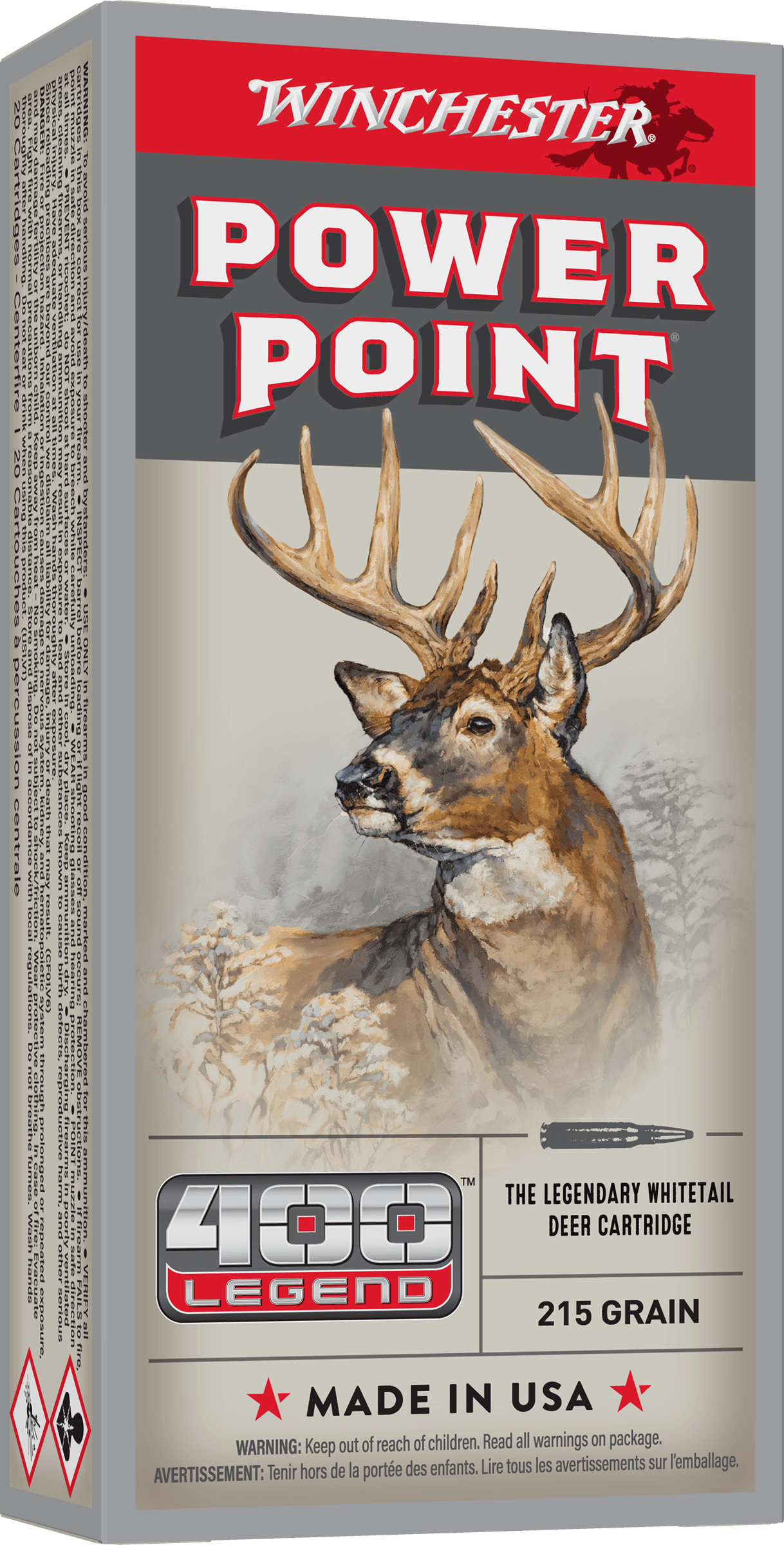

John M. Olin, the longtime head of Winchester following his father’s purchase of the company in 1935, shared Darling’s concerns about the conservation of waterfowl; and to that end he established NILO Farms in Southwestern Illinois as a showcase for hunting, conservation, and gun dogs. Like Darling, Olin was convinced that reliable retrievers were the key to reducing the loss by hunters of ducks and geese, and upland game, too. To prove it, he began a to produce the finest retrieving dogs in the nation.

The greatest of NILO’s retrievers, however, started out as a question mark. The black Lab King Buck, was yet another Iowan. The same year as Reece’s painting of buffleheads became his first winning duck-stamp illustration, a dog was born and was soon fighting for his young life. Supposedly vaccinated against distemper he and one of his litter mates came down with severe cases of the disease when they reached their first buyers in Omaha. While the other pup soon died, King Buck, as he would come to be called, enjoyed a different fate. His owner kept him for a month in a warm basement, near death in his basket. Then one day when the owner came down to check on him, the pup was standing, if only weakly.

The King, after a long recovery, was 18-months old before he began to hunt, the owner noting his hard work and strength in the water. Unable to afford entering the Lab in field trials himself, his owner sold him to someone who could. But the King ran hot and cold in the contests into which he was entered. He nonetheless caught John Olin’s eye, who in 1951 over the objections of his head trainer-handler, Cotton Pershall, purchased the King at age three for the rather princely sum, then and now, of $6500.

The rest is well known. After more mixed performances, King Buck started his winning career, scoring two consecutive National Field Trial Championships, becoming in 1953 only the third repeat winner. He went on to compete, complete, and win scores of other contests; while turning into the Babe Ruth of field trials, though, he continued, perhaps most importantly,in his role as John Olin’s best and favorite hunting dog.

Olin wanted to emphasize the importance of retrievers in sustainable waterfowl hunting, so he supported the efforts of conservationists to urge the Department of the Interior to make a retriever the subject of the 1959 duck stamp. And then he invited Reece, whom he had indirectly been introduced to by Darling, out to NILO to see King Buck at work. It took two retrieves for Reece to find his inspiration.

On bringing back a second duck, King Buck’s eyes had an expression Reece could not shake. And that is what he recreated for, and that is what won, the stamp contest for 1959. “The Dog” as it is called, went on to become the most popular image ever for duck-stamp art prints.

NILO Farms continues to offer premier clays and wingshooting, today to the public. Sharpen your eye on the range and from now to March take a day to follow the legend of King Buck and Maynard Reece into the field behind fine dogs for guided hunting for pheasant, explosive chukar, and flighted mallards. Leave time for a delicious lunch and don’t forget your birds, cleaned and frozen for you to take home.

When you’re at NILO, be sure to visit the statue in honor of King Buck who died in 1962. Reece lived on, and painted on, for almost another half century. And for the marvelous art he left behind, the honor is all ours.

A world leader in delivering innovative products, Winchester is The American Legend, a brand built on integrity, hard work, and a deep focus on its loyal customers. Learn more about the history of Winchester by visiting Winchester.com or connect wit us on Facebook at Facebook.com/WinchesterOfficial.